- Home

- Peter Joffre Nye

The Fast Times of Albert Champion Page 6

The Fast Times of Albert Champion Read online

Page 6

Net profit supported him and Madame Celeste Clément, their two sons, the oldest also named Albert, the other Marius, daughters Jeanne and Angèl, and his staff of servants in a grand residence across town at 35 Avenue du Bois de Boulogne—an address with status.25

Like many Parisians, Clément and his wife had a passion for opera. To ensure access to tickets for opening nights of new productions of works by Georges Bizet, Jules Massenet, or revivals of Jacques Offenbach, Clément bought the land for construction of the new Paris Opera House—securing his place of importance not only as manufacturer but also as a patron of the arts.26

While Champion picked up information about his boss, he shared some of his background. Clément understood what it was like as a child to lose a parent, having lost his mother when he was seven. He assessed the youngster as deserving a chance to develop his talents. In Clément, Champion gained a tutor, albeit a rather driven man who put his work before family, which Champion came to assess as a consequence of constantly pushing his business ahead of the competition.

Clément subscribed to trade journals, some from England, to keep up with developments. He would have chortled with Gallic hubris, informing Champion that so many English words derived from French that Champion could easily get the essence of the articles. Since William the Conqueror of Normandy had overwhelmed English troops in 1066, everyone in the courts and wherever commerce took place spoke the language of the conquering French. So the trade press in England, Ireland, and the former colony in America relied on French vocabulary, such as attention, courage, important, agent, surprise, plus, extra, minute, idiot, silence, urgent, problem, and solution. The Irish, the English, and the Americans all spoke French now.

Robust sales of la petite reine stirred two Montmartre craftsmen to think up something radical. Réne Panhard, a graduate of the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures,27 and Émile Levassor, a businessman, co-owned a company that manufactured machines that cut and shaped metal.28 Panhard had bought French rights from Gottlieb Daimler of Germany to make internal-combustion gas engines.29 Daimler had fitted an engine under the driver’s seat of a carriage, creating self-propulsion in 1885.30 He turned the machine with a tiller that substituted for reins. Daimler saw his invention as a horseless carriage.

Panhard and Levassor improved on Daimler’s design. The Frenchmen mounted the engine on the chassis front and replaced the standard leather-belt drive with a metal shaft-and-gear transmission, which included a clutch that allowed the driver to change speed ratios as the vehicle sped up or slowed down.31 To cool the engine, Panhard and Levassor added a radiator.32 They introduced a round steering wheel for making turns. In 1892 they introduced the archetype modern automobile.33

Clément had a historical perspective on the long competition between France, England, and Germany for leadership in the quest for self-propelled vehicles. During the early nineteenth century, adults and children alike in all three countries had rolled around on hobbyhorses with two wooden wheels under a board slab. Riders sat on the slab and moved by scooting feet on the ground. Paris coach maker Pierre Lallement in 1860 had attached pedals to cranks that fit to the front-wheel spindle of a hobbyhorse.34 It had iron-rimmed wheels made of chunky wooden spokes and straight iron handlebars that turned the front wheel. Lallement’s leather saddle attached to a steel spring fastened over the frame. He named his invention a vélocipede, the prototype bicycle. He had a stint producing vélocipedes with Pierre Michaux and son Ernest, builders of baby carriages in Paris. Then the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 had dealt vélocipedes a fatal blow.

Yet creative minds continued to mull over some kind of machine enabling people to get around on wheels. For years steel had been made from iron, but it was expensive and available only in limited quantities, measured in pounds, for making tool bits and swords. English engineers led by Henry Bessemer in Sheffield refined the iron-making process to produce cheap steel in quantities that sold by the ton for constructing bridges and buildings.35 The advanced miracle steel enabled Eiffel to build his iconic tower and had applications for improving bicycles. English steel could be drawn, hollowed for lightness, and shaped while retaining its tensile strength.

Artisans in Coventry, in England’s Midlands, took advantage of Lallement’s concept and the advent of improved steel. In the early 1870s, they increased the size of the front wheel and fashioned long steel spokes with steel rims on a bicycle frame of lighter, hollow tubing. They created the high-wheel bicycles, which thrust England ahead as world leader in mechanical personal transportation.36 Local artisans introduced more advancements, including the modern bicycle with a chain drive and both wheels the same size on a diamond frame. Bicycle manufacturing poured money into the Coventry’s economy. The city that had been renowned for Lady Godiva once riding naked on a snow-white horse through the town at noon had a thriving business in transportation.

Then Panhard and Levassor initiated a critical advancement that made Clément’s entrepreneurial juices run. He felt that the progression from vélocipedes to high-wheelers to safety bicycles to Daimler’s horseless carriage culminated in the Panhard-Levassor automobile. Clément put his resources behind Panhard and Levassor to make certain they won the commercial war in personal transportation for France. Clément invested heavily in their company and made sure its autos were equipped with Dunlops.37 He was appointed director of the corporate board.38 Clément felt sure the future of individual transportation was in autos.

At some point Champion encountered twenty-nine-year-old Henri Desgrange, a former law clerk with writing aspirations, employed then writing ad copy and handling publicity for their boss, Clément. Desgrange came from money, and the security he drew from it conferred on him a religion of might. In photos a bearded young Desgrange stared defiantly into the lens, arms akimbo, chin jutting, demeanor brazen. “His motto could have been Vae Victis (woe to the vanquished),” observed journalist Roger Bastide.39 When Desgrange stood near Clément, his employer came to his chin. Desgrange wrote in his office near the bookkeepers at the rear of the factory on rue Brunel, pen scratching across reams of paper, pausing only to dip his steel nib in an ink well. He dispatched Champion, as courier, to printers, artists, and journalists.

Desgrange had established the first world hour record (for distance pedaled over sixty minutes around a track).40 He had good legs and pushed himself with focus, hard work, and audacity. Before anyone better, Desgrange had acted. Clément acknowledged him as a maverick. Desgrange became one of Champion’s influential models for how a young man might change his life through cycling and realize grand ambitions.

Champion’s courier runs on one of the house beater bikes inevitably had him cruising along Boulevard des Batignolles, bordering the southern edge of his neighborhood. Shops standing shoulder to shoulder catered to all the indulgences of Parisians and troops of tourists from around Europe, Great Britain, and America. Riding in the sun’s glare, his reflection on the shop windows kept him company.

Boulevard des Batignolles exerted a lasting effect on Champion. A fashionable grocer at number 86 gratified epicurean palettes with a selection of wines as well as a delicatessen with fresh fruit and vegetables from the continent.41 The shop was operated by Bernard and Marie Delpuech.42 There one afternoon he encountered their daughter, Julie Elisa, counting change for customer purchases. Family and friends called this willowy, dark-haired jeune fille, Elise. She was tall, standing eye to eye with Albert, with fine features, a small chin, and eyebrows drawn sharp like a Modigliani model. She had long thin arms and legs and delicate fingers. Albert, dashing around Paris on his courier’s cycle and stopping to swagger into the wine aisle with confidence rolling off him, attracted her interest. He began to court this daughter of the merchant class, a rung above his station. He found her chic—a catch.

Champion’s career-making tryout in the race in the Palais des Arts Libéraux and his eighteenth birthday on April 5, 1896, fell on the same Sunday, as though he were bestowed a gift. Where the

Palais had once held exhibits of the liberal arts for the 1889 world’s fair, including medicine and surgery, theater, and transportation, it now held Champion’s professional debut.

Pierre Tournier, as manager, fussed over Champion and the three-rider triplets to mollify their prerace jitters. The audience filling tiers of seats created a wall of voices. The announcer on his megaphone kept up a patter. A band in the middle of the infield filled the air with popular tunes. Riders were whizzing around the track in the preliminaries. Through the distractions, Tournier spoke calmly to his crew, methodically took care of the mundane tasks of pumping up all the tires, making sure everyone on the team had properly signed up with officials, and tying the competitor cloth numbers securely around their upper left arm for easy spotting. He kept Champion and his pacers attentive.

Champion would be tested. Win or lose, the outcome would determine his future. Expectations were high for him. Some journalists compared him with Jimmy Michael, the diminutive Welshman pace follower and world champion who drew crowds that packed every track in Paris and around Germany to standing room only.

The race was organized by Henri Desgrange.43 He put on weekend events to realize his ambition of one day creating the world’s greatest sports extravaganza.

“He’s called Champion, a strangely prophetic name for his future battles,” Desgrange wrote for Le Cycle under the nom de plume A Spectator of the Third Arrondissement, caricatured on the margin of the page as an aristocrat in top hat, frolicking on a bicycle, coattails flapping.44 “It’s a bit like the crowning of the winner coming before the event itself. Physically, the young rider is not very attractive. I would even go so far as to say that he’s not very appealing.”45 He chided Champion for having a sultry expression and wearing an ill-fitting purple jersey: “Some riders show off their shape, show off their muscles and their suppleness, but Champion hides his spindly legs and pulls his jersey as low as possible to cover them up.”

Champion and three rivals lined up next to one another along the breadth of the banking. The triplet teams waited behind them. Tournier bent low at the waist and with both hands held Champion steady on his Clément cycle. When the official in a silk top hat fired the starting pistol, Tournier gave Champion the traditional push off like a shot-putter. The triplets came around wide on the track for their riders to catch rear wheels and they were underway.

Champion charged to the front early. He had a fierce drive to prendre le pouvoir, to take supreme power, like Napoléon. Champion not only rode fast, but he added a showman’s flair—he sat up straight, like the unicyclist he had been, and put on an intimidating exhibition of speed and bike handling.46

“He simply took his hands off the wheel and, by a skillful jerk of the knee, he regained the balance he had momentarily lost, all in the flash of an eye,” a reporter cited.47

When he dropped back down and grabbed the drops of his handlebars, he made a graceful switch to catch his relief triplet.

“His mastery of pacing and competency in switching from one pace team to another exceeded his experience,” claimed one account.48

As the number of laps wound down, Champion sped behind his triplet teams like a courier fearful of getting sacked for tardiness.

The ringing of a cowbell to announce the final lap roused the audience in the Palais to jump up and down and cheer Champion. The noise level created a wall of sound. It blocked out all his pain and made him spin his legs faster.

Approaching the finish line, he leaned deeper and faster into the turns to live up to his name. He whipped down the back straight to impress his jeune fille Elise. He zoomed around the final turn for extra cash to take home to his mother and brothers. He flew across the finish line for victory and la gloire!

“He turned in a masterpiece,” a journalist wrote. “The rookie’s victory was complete and convincing.”49

On his victory lap, Champion waved the bouquet of flowers he received to show the audience his gratitude. The francs he won fit in his fist, a down payment on the fortune he needed—if he could follow his dream. He took the money home to his family. He kept la gloire for himself.

The next morning, Clément dispatched him to the studio of Jules Beau, a prominent portrait photographer. Taking his Clément cycle into the studio, Champion smelled the chemicals and eyed mysterious paraphernalia. Beau’s apprentice, who signed his work as Bauenne, set up a camera on a tripod. Champion posed on his bicycle in profile for one image and then gripped the handlebar drops and glared at the lens as though to challenge the world.

A print of Champion ran with A Spectator’s story in Le Cycle.50 The magazine devoted a full page under the banner “Le Coureur Champion.” The coverage was all about him, as though his opponents had failed to count: “He is a small rider on a small machine, with small legs which turn short cranks, but will achieve some great performances, because Champion only just began to find his voice in his race last Sunday. We will have to wait and see him begin to shine with the kind of brilliance that will perhaps put even Michael in the shade.”51

At age eighteen in 1896, Champion’s speed and riding skill prompted a reporter to write that he had extraordinary audacity and rode like a beautiful devil. Photo by Jules Beau. Courtesy of Cherie Champion.

Champion immediately nabbed the spotlight of the sports world. Bestowed with a Clément team jersey with a rooster on the back, which fit better, and a contract from the Roubaix Vélodrome, Champion raced as a regular in cycling-mad Roubaix, a textile city some 170 miles north of Paris, in northern France near the Belgian border.52 Roubaixians, known to work hard six days a week in the mills, spent Sundays watching their favorite racers at the cement outdoor vélodrome. Roubaix had so many mills it was known as la ville aux mille cheminées, the town of a thousand chimneys.53 Here Champion experienced the trial-and-error seasoning required of every young pro cyclist: defeats and victories.

Champion inhaled the cheers of the spectators, taking in their adulation like oxygen. “The kid was marvelous,” a journalist wrote.54 “He began to dominate right away. The little demon was soon tearing down the track like a torpedo behind triplets and quadruplets and no one could beat him. He knew only victory.”55

He grew stronger with confidence and savvy. He was dubbed the “Human Catapult” by a journalist who wrote that he “didn’t know his own strength and showed himself to be more and more a man of some class.”56

Many in the press corps remarked on his superior handling skills. “At the old, almost flat, Buffalo [Vélodrome], he aroused general admiration by his impressive turns,” a reporter noted.57 “At the speed he went, his two wheels slid dangerously. He flew by anyway, fearing neither God nor the Devil.”58

Racing was about making money for the dual compelling needs that invigorated him. He gained financial support for his family and the ego endorsement enjoyed by entertainers and politicians. As his ego grew, he needed to impose himself on crowds of strangers and win their love. Each race he won was greeted immediately with audience approval followed by a bouquet of flowers, a victory lap, then a cash award. Champion also craved Elise’s attention, and winning elevated him in class as a suitor for her hand.

As Champion soared like a comet, Clément directed construction of a massive factory in Mézièrs, an ancient fortified town on the Meuse River in northeast France, with a bustling commercial center and network of railroads. He facetiously named the facility La Mercerienne, a haberdasher’s shop, to make custom spare parts for bicycles and Panhard-Levassor autos.59 Clément selected Mézièrs for his new factory in homage to the heroic knight Pierre Bayard.60 He erected a statute of the knight in front of La Mercerienne.61

Clément’s fortunes were soaring. The one hundred shares of Dunlop stock he had purchased for 5 francs a share were now selling for 7,500 francs each.62 He was an early advocate of the capitalist notion that the best way to deal with competitors is to make them an offer they cannot refuse and then buy their business. He advertised on posters that he had capital of 4,0

00,000 francs—letting the row of zeroes separated by commas scream his worth.63 He negotiated with Alexandre Darracq to purchase Gladiator Cycles.64 In turn, Darracq used the money to found the Darracq Motor Company.65 Clément also bought Humber and another maker called Phebus (a synonym for the sun), and merged all three to create the largest bicycle production company in France, Clément Gladiators.66 What better advertising for Clément than Champion riding a Gladiator with Dunlops?

Adolphe Clément bought out his business rival Gladiator Cycles and boldly promoted Gladiators with cheeky advertising. Image courtesy of Poster Photo Archives, Posters Please, Inc., New York.

On August 24 Clément sailed from the Normandy seaport of Le Havre on the English Channel, aboard the French liner La Bretagne, to New York.67 His intention was to scout out the American scene, and he included a visit to Colonel Albert Pope at his corporate headquarters in Boston, Pope’s huge bicycle manufacturing plant in Hartford, and other manufacturers.68

Prior to his shipping out, Clément received a visit from the English trainer, James “Choppy” Warburton, on the prowl for his next big star, a vedette. Warburton, impeccable in a swallowtail coat, a diamond stickpin in his silk scarf, and a bowler, had developed Jimmy Michael into a world champion pacer. But the two had had a falling out, and Michael sued him for doping his drink. Then Warburton sued Michael in London for libel. The Englishman, in search of a new Michael, had determined that of all the young prospects in Great Britain and France, Champion’s talent stood out as the most glory-bound.

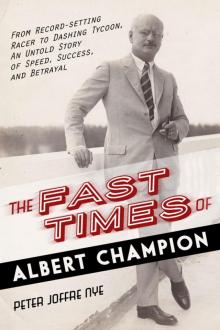

The Fast Times of Albert Champion

The Fast Times of Albert Champion