- Home

- Peter Joffre Nye

The Fast Times of Albert Champion Page 5

The Fast Times of Albert Champion Read online

Page 5

Champion was getting inculcated with a mix of sport and a life, shot through with an unrelenting exercise regime, a stern work ethic, pride, tradition, and ignorance. Old tales accepted as gospel prohibited swimming because water softened muscles.38 Bathing in warm water opened pores and let in diseases. Getting a haircut carried the risk of catching a cold. A winner never washed his jersey or shorts to keep the good luck, a superstition that made generations of athletes adamant about wearing smelly, sweat-stained clothing, to the annoyance of their families.

He experimented with drafting—riding close behind the rear wheel of the cyclist ahead, whose front wheel, face, shoulders, and chest divided the air like the bow of a ship pushing through water. When the finish came in sight, followers had fresher legs and whipped ahead of the leader as though thrust by a slingshot. Racing was a confluence of fitness and tactical skills.

Clément continued to make news that impressed Champion. The manufacturer constructed an outdoor five-hundred-meter vélodrome with a big grandstand and bleachers the rest of the way around near rue de Courcelles, a stone’s throw from the Seine in the northwest suburb of Levallois-Perret. The track opened in August 1893, christened as Vélodrome de la Seine.39 Behind the cheap seats along the back straight stood a row of wooden cabins for racers to change clothes and store bicycles and equipment, along with the latest thing—a building offering cold showers.

London’s To-Day called the vélodrome “a splendidly made cement track, and every Sunday the enclosure is thronged by ten to fifteen thousand persons, who assemble to witness the exciting contests. French, English, Dutch, German, and Belgian riders competed in the races, and the sport is of a truly international character.”40

Near the vélodrome he added a plant to manufacture Dunlop tires. His new factory was powered by steam engines with five-hundred-horsepower (500-hp) capacity. A cafeteria offered ovens for employees to warm food they had brought.41

Yet Clément kept expanding his empire. Major railroad companies serving travelers from Paris to cities all the way south to the Riviera on the Mediterranean Sea contracted Clément to supply their legion of workers with cycles. He bought an abandoned factory in Tulle, the south-central city that gave its name to the stiff fabric used for veils and ballet costumes.42 Clément converted the building into a division of his Paris operation to produce cycles. Depending on the season, his Tulle plant employed up to one thousand workers.43

In the spring of 1895, seventeen-year-old Champion gave up the job of instructing clients how to ride. He left Fol to present himself to Clément and Company on rue Brunel, conveniently close to where he lived.44 It is likely he had passed many times past Clément’s sign of the rooster on a wheel hanging over the front door.

The window on the street displayed new cycles with enameled finishes that glinted even in the grubby light of Paris’s chronically overcast skies. Clément and Company had taken over the Saint Ferdinand Building, at 18 and 20 rue Brunel, after Jules Chéret had decamped with his atelier and print shop to a new venue a few blocks over. Champion may have been unaware the building was named in tribute to the thirteenth-century Spanish king sainted for taking care not to overburden his subjects with taxes, something that appealed to the sensibilities of Clément.

Champion stepped under the sign of the rooster and pushed open the door. He entered the factory intent on securing a job, oblivious to how it would become his school.

CLÉMENT IS A HOUSEHOLD WORD.

—WESTMINSTER BUDGET (LONDON), OCTOBER 9, 18961

Once inside the St. Ferdinand Building, Champion’s nose was assailed by the pungent smells of oil, grease, lacquer, and acetylene laced with sweat and nicotine from about 150 laborers and artisans cutting steel, brazing frames together, and painting frames to produce finished petits reins. He heard the whirring and flapping sounds emanating from a forest of long leather belts, four or five inches wide and thick as fingers, connected to pulleys high overhead feeding power down to run machines at workstations on the concrete floor—the universal clatter of nineteenth-century steam-powered factories.2 He encountered the floor manager, in a dark smock and flat wool cap, a cigarette burning in a corner of his mouth, and received his once-over.

It may have struck Champion that he stood where countless other candidates had, only for the majority to fail. As he began to present himself, mentioning his name, the floor manager raised a hand—no need to say anything more. It seemed his audition ended before he drew his first breath.

Instead, he found to his surprise that at Clément Cycles, they already knew Albert Champion.3 They were looking for someone with his list of amateur victories—referred to as palmarès. He was offered a sponsorship to race as a pro for Clément Cycles the next spring season. The prize money was going to be his to keep, like a prizefighter on wheels.

He would have a new racing cycle—built with a modern diamond frame and lighter than the one he had bought, plus all the Dunlop tires he needed. Even better, Clément Cycles offered to provide a pair of three-seat triplets and six riders to pedal them for Champion to pace behind for faster workouts. He had the autumn and winter to get race ready. He would try out in the twenty-five-kilometer (15.6 miles) paced race serving as the new season opener on the first Sunday in April,4 at the winter indoor vélodrome in the Palais des Arts Libéraux, a massive marble building near the Eiffel Tower. If he performed as expected, he would receive a Clément team jersey with the trademark rooster across his back and race full-time for Clément. Champion would be on his way to garnering honor, fame, riches, and la gloire!

The offer was bittersweet. For the next five months, when he wasn’t training for his tryout, he would earn his keep by working as a bicycle courier, copying Clément’s handwritten correspondence with a delicate letter-copying book process, and performing odd jobs—all for a weekly salary of 6 francs.5 The pay was meager, a substantial cut in income. He still had to support himself and help provide for his mother and three younger brothers.

Champion, not inclined to ponder negative prospects, seized the positive, his opportunity to ride as a pro for Clément.

Guiding him into his new métier was Pierre Tournier, a wiry gent in his mid-thirties dressed like a banker, his swank felt hat tilted at a jaunty slant.6 Tournier had a certain way of getting along with people of all types of personalities.7 Clément put him in charge of sponsored riders to ensure they had the Dunlops and whatever supplies they needed—when they succeeded, so did the manufacturer. Tournier would have arranged for Champion to receive a new racing cycle, all steel except for a leather saddle and rubber Dunlops. The frame had modern straight lines of the diamond shape as well as curved handlebars clean of any attachments.

Pierre Tournier, far left in the back seat, enjoys a smoke, sitting next to American national cycling champion Harry Elkes (middle) and Arthur Zimmerman, world cycling champion and US champion many times over. Tournier shepherded them around Paris in 1900 to see the sights in a Clément-Talbot motorcar. Photo by Jules Beau. From the collection of Lorne Shields, Thornhill, ON, Canada.

Champion’s new job involved learning how to ride the steeply banked indoor board track, a saucer ten laps to the mile, or 176 yards around, in the Palais des Arts Libéraux.8 The vélodrome was surrounded by box seats at the start/finish line. A few tiers of seats surrounded the track. There was a judge’s stand in the infield at the start/finish line and a bandstand in the middle of the infield. The vélodrome and stands took up only a small portion of the facility, languishing after the 1889 Paris Exhibition. The vélodrome’s banked turns of thirty-eight degrees and straights of fifteen degrees looked daunting.

Tournier instructed Champion to follow experienced cyclists tacking a diagonal angle up the banking, moving as easily as dancers on a stage, to near the top edge’s wooden rail, about twenty feet high, before diving down to build speed. To spectators, the precipitous banking appeared like a wall. One of the first things Champion learned about vélodromes, however, is that onlookers see a trom

pe l’oeil. Cyclists appeared to lean precariously as they flashed through the turns, when both rider and machine actually remained upright over the surface at all times, as though traveling straight on a flat street. The illusion added to track racing’s mystique.

Champion became comfortable whizzing around laps before Tournier had him progress to pacing fast behind the triplets.9 First Champion drafted with his front wheel close behind the rear wheel of his team on a three-seat machine, clocking off fast times on the lower end of the vélodrome while the second team cruised the upper rim. After three or four laps, the legs of the first team grew tired and the riders angled up the banking to recover as the second team, with fresh legs, descended for Champion to catch their draft for nonstop highballing.

Scarcely a week went by before the former unicyclist entertained himself by rubbing his front wheel against the rear wheel of his pacing machine in the turns, shaving the triplet’s speed and disturbing its equilibrium.10 It was a reckless yet fantastic stunt.11 Pacing cyclists always guard their front wheel at all costs, like a boxer’s arms and fists guard his face. Overlapping wheels were by far the most frequent cause of crashes. In the blink of an eye, the slightest false move could cause Champion and the triplet to topple over at the expense of torn clothes, abrasions, bruises, or worse. Speeding around the saucer called for a change of balance about every fifteen seconds, into and out of the next banked turn, then on the straight, for thirty-second laps. There were infinite opportunities to make a mistake. Yet he never fell down. He liked showing off.

“The game was not without danger, but Champion got a kick out of it,” noted one observer. “He had extraordinary audacity.”12

The press became alert to Champion’s exceptional talent. Rubbing wheels was part of his debut preparation. In competition, there was no such thing as “good enough.”13 He was adding a skill of the trade to make him into a winner, like Charles Terront. He planned to win his try-out race in a handsome fashion.

Champion’s workouts were usually in the mornings. The rest of the time, from Monday through Saturday, he arrived at the factory by six o’clock,14 in time for the Angelus devotion, the triple-stroke bell ringing repeated three times in the ancient stone Saint-Pierre-de-Montmartre Church. He opened the heavy window curtains. He swept and dusted around numerous workstations with lathes, drill presses, milling machines, and the benches holding heavy vises and clamps.15 He swept the back-room offices of the bookkeepers and dusted their leather-bound ledgers standing on shelves like financial soldiers at attention. He built the hearth fires to ward off morning chills, wound the wall clock, split kindling, and carried coal that ran steam-powered machinery. Sometimes he washed windows. When the laborers and office employees arrived at seven o’clock, they found everything ready. Then he was free to meet his pacers at the Palais for their practice sessions before he returned to the factory.

At twelve o’clock, the church bell rang the noon Angelus. Workers donned hats and lit cigarettes they hand-rolled. The factory emptied for traditional two-hour lunches by the ringing of the ninth bell. Champion grabbed his cap and beat it home for lunch with his mother, taking her customary break to return home with his brothers. By two o’clock he and others sauntered back to work.

At six o’clock the third Angelus rang, signaling the workday’s conclusion. He closed the window curtains and left.

The only exception in the routine was Saturday afternoon. Champion joined shop boys lining up outside the bursar’s office in the rear of the building. He received a pay packet of 6 francs. He carried his francs home at once to his mother, a welcomed addition to their slender family income, as he awaited his debut to earn 100 francs as the race winner.

More bicycle manufacturers and deeper economies of scale drove down prices and increased sales. Advertising took on an increased premium in the hurly-burly of escalating capitalism. The enormous success that Chéret’s beguiling Chérettes wielded in retail sales impelled Clément to commission posters of carefree ingénues, naked or clad in diaphanous negligees, sitting atop their Clément cycles or flying like angels, holding his two-wheelers, over the Paris skyline. Flirtatious, bare-breasted beauties with fresh makeup implied the bicycles were light as air and easy to ride. To traditionalists objecting that women lost femininity when they indulged in physical activity, the posters shouted au contraire, cycling added to feminine allure.

Clément hired Paris’s renowned artists such as Jean de Paléologue, who signed his posters PAL. His classical art studies in London and Paris had nurtured his flair for making women practically leap off the paper. He selected well-endowed models and depicted them as Greek goddesses in states of déshabille, frolicking in skimpy, sheer gowns. They exposed considerable flesh and sold great sex appeal. Another artist Clément relied on was Ferdinand Misti-Mifliez, who signed his work Misti. His brush strokes reflected Chéret’s lightness.

Telephones were coming into use, but not with artists. Clément sent Champion as a courier carrying proposed designs back and forth between his office and artist ateliers.16 On his courier runs Champion would have encountered de Paléologue and Misti in their ateliers, a shaft of brightness pouring through a skylight. Usually the object under the light was a young woman posing, either in the nude or déshabille, standing, or ensconced on a chair, surrounded with discarded clothing or gossip sheets Echo de Paris and Psst! Deft brush strokes transferred facial features, shoulders, hips, and breasts onto the canvas with playful, even magical, touches. On walls and kiosks all over the city, a blonde goddess of Paléologue in gossamer dress falling off her shoulders defied gravity and soared in the colorful dawn pastels over the Paris skyline. She brandished a laurel wreath of victory in one hand while her other gripped a Clément cycle.

As soon as the artists painted their posters, Clément ordered couriers to expedite them to printers. Shrewd about how he spent money, he took care not to rely on just one printer. He used several so as to get the best deal and quickest turnaround. Once off the presses, stacks of poster advertisements were distributed to a fleet of couriers, including Champion, armed with glue pots. They fanned out and plastered posters on surfaces all over Paris, a city of posters.

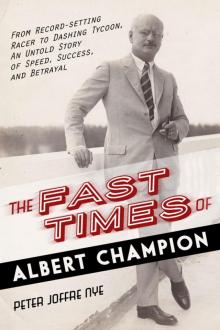

Adolphe Clément gave Champion pointers for advertising to promote products. Champion gained notice in America racing on Clément Cycles. Image courtesy of Poster Photo Archives, Posters Please, Inc., New York.

These activities kept Champion couriering throughout Paris, crossing its many bridges that spanned the meandering Seine, to deliver written or oral messages. In this way, he made personal contact with artists, business leaders, laborers, and government bureaucrats—getting comfortable with the people operating the business arena.

Champion had entered the urban workforce as the Second Industrial Revolution picked up tempo. Machinery and manufacturing surpassed the longstanding domination of the agrarian economy. He had the good fortune to work for Clément, who took pride in a paternal interest in his workers, as Bayard had cared for the well-being of his troops. All machines, including those cutting wood, were equipped with ventilators to remove dust and prevent damage to workers’ health.17 Champion had joined a new order.

Clément was exchanging letters with power brokers around France and across Europe, which led to Champion learning how to master the letter-copying book process.18 A ubiquitous piece of nineteenth-century office equipment was the screw press—the copier machine of its day,19 which made tissue-thin paper copies of correspondence that Clément wrote longhand. The screw press squatted on a table of its own in Clément’s office in the back of the factory. It was a magnificent machine, made of cast-iron parts painted a uniform black lacquer and decorated with gold-leaf fleur-de-lis, the heraldic emblem of French kings, with stylized three-pedal iris flowers. The handle on the middle of the top spun a spiral shaft that lowered the upper plate onto the bottom flat plate for the paper to make an impression.20 Turning the handle so the plate made soft contact with the paper made only a faint copy, or failed altogether;

tightening it too hard made an illegible blob. Champion had to turn the handle to the proper tension to get it right.

He was instructed to begin the delicate procedure by dampening a sheet of imported Japanese rice paper, prized for its strength and ability to absorb ink, with water from a brush, or a blue cotton cloth with serrated edges soaked in water.21 The acid-free sheets of rice paper were numbered in sequence up to a thousand folios in a leather-bound volume, containing an index. Champion inserted the letter intended for reproduction in the bound volume, insulated the wet page from adjacent dry pages with sheets of oiled paper, and set the volume on the bottom flat plate. Copies were made by turning the handle, which lowered the top plate.22 To get the proper pressure without spoiling the original letter while making a clear copy required a knack. Copies stayed in the leather-bound volume; originals went into envelopes for posting. He had to practice before passing.

Champion came to appreciate his boss’s fascination with the great knight Pierre Bayard. Clément likely had a painting displayed on a wall of Bayard in a suit of armor, visored helmet in the crook of his left arm, right hand gripping a lance. Bayard was killed in action in Italy in 1524 while leading troops for Francis I.23 Bayard’s body was returned to France and interred in Grenoble.24 Clément would have mentioned a pilgrimage he had made to the knight’s memorial and ancient family estate, Chateau Bayard.

When Clément sat at his desk to pore over the accounting ledger, he had occasions to instruct Champion about the intricacies of commerce. Payments received from the sale of bicycles, tandems, and tricycles to distributors as well as royalties from the Dunlop tires generated gross revenue. From that, Clément deducted the costs of material, labor (including Champion’s paltry wage), and the building rent. The difference was his company’s gross profit. Clément tallied all operating costs—from the purchase of firewood and coal to installation of electricity (which increasingly took over from steam power to operate machinery) to advertising expenses—and subtracted them from the gross revenue, which left Clément with a net profit.

The Fast Times of Albert Champion

The Fast Times of Albert Champion